How we saved $3k a month on GitHub LFS Bandwidth

Greetings, tech adventurers! Ever wondered how to transform a digital challenge into a cost-saving victory? In this post, we’re about to unveil an ingenious solution that not only streamlined Git LFS bandwidth but also slashed costs by $3,000 a month. Get ready to dive into the world of reverse proxies and Amazon S3, where a bit of tech wizardry led to remarkable transformations in the realm of software development. Let’s embark on this journey of innovation and cost-effective magic! 🚀💰🔮

One thing I learnt during my time at Vela Games and coming from E-Commerce and SaaS companies is that games are just different and because of that, they require special solutions on things that you wouldn’t think about in other situations.

Games are BIG, especially live services games that require new content to be added onto the project constantly to keep players engaged and would be expected to keep increasing in size for years and years.

When Evercore Heroes was first conceived as an Unreal Engine project we decided to use Git for Version Control, and specifically use GitHub as our Git Server solution. But going back to what I just said, games are BIG and filled with binary files. GitHub has file size limits, it warns you when you commit files larger than 50MB and just outright blocks you if you try to upload a file larger than 100MB, and this all is born from the fact that Git is not great at handling large binary files.

So the Git Large File Storage (LFS) was created to try to mitigate this issue, instead of tracking binary files in the Git repository a pointer to the binary file is created, and the actual binary is stored on a remote server, services like Github provide their own LFS storage service as part of their offerings. When a git checkout the git client uses the calls the LFS API to query for all the binary files and downloads them.

Now Github charges you for both storing files on LFS and also for bandwidth, and I keep squeezing the CircleCI card here, you can read all about it in this post if you haven’t done so yet. Due to the work we did, the size our game was achieving and the growth of the development team, we were constantly reaching the maximum bandwidth allocation we had and had to keep buying data packs for it. We were consuming bandwidth for both local development machines pulling from git but also each time the CI pipeline ran, and to give you some quick maths here just to add on some drama and to piggyback a bit from the clickbait title of this post:

- The average binary content of our game (not the total LFS storage we have for all asset versions) is 25GB

- Checking our CI metrics, last month we had 1300 pipeline runs, each one of these checks out the game repository, and sometimes more than once on a single run but let’s say it’s just once. That is \(25GB * 1300 = 32.5 TB\)

Now Github is changing its pricing model for LFS Storage and Bandwidth starting September 1st, 2023.

Let’s calculate the cost with the current pricing model, each data pack costs $5/mo and provides 50GiB of bandwidth per purchased pack. So we would need \(32500 / 50 = 650\) data packs costing $3250/mo

The new pricing model is metered and charges $0.0875 per downloaded GB so that’s \(32500 * 0.0875 = 2843.75\), still almost $3k/mo

My Manager probably

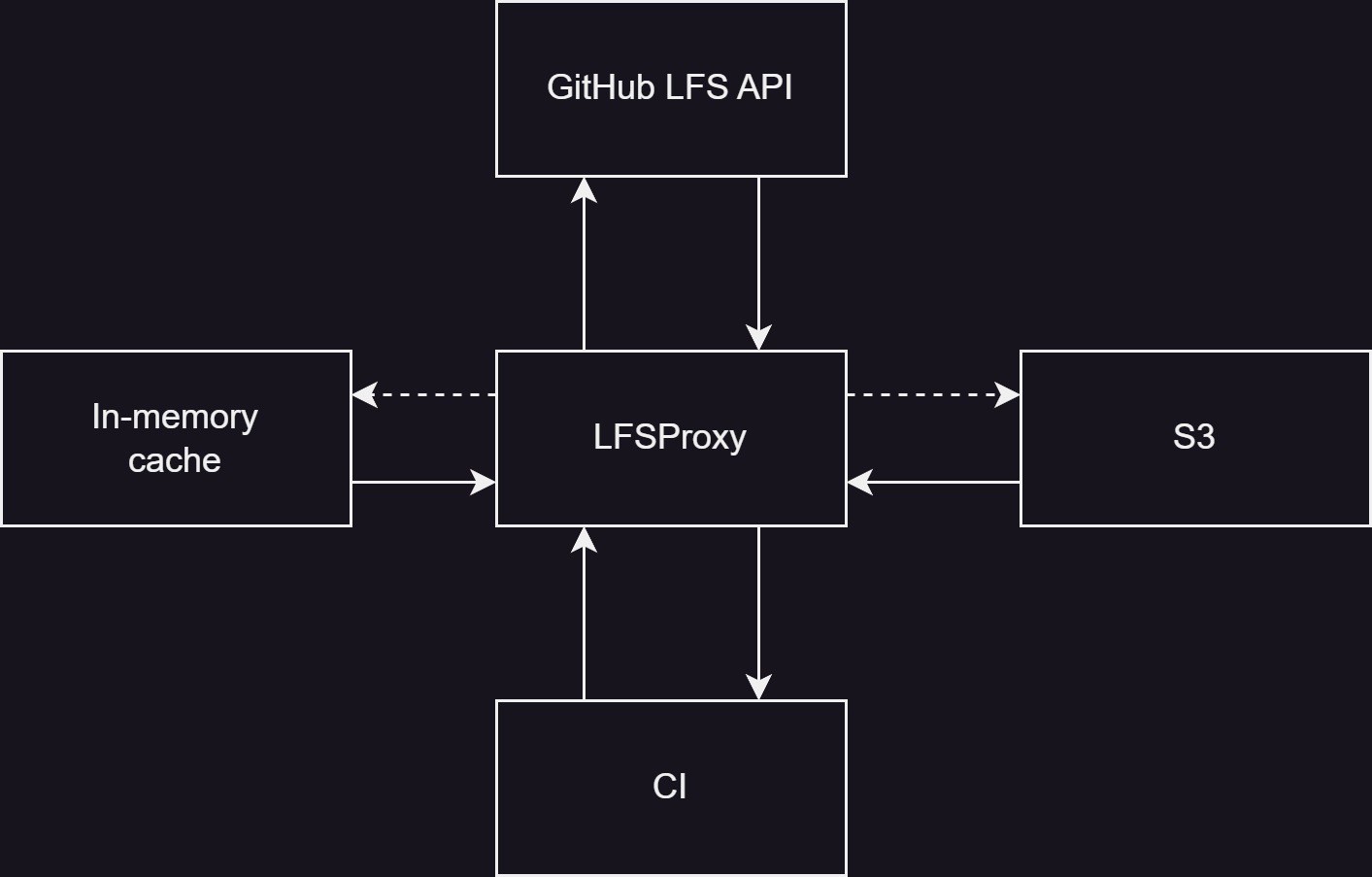

So we needed to do something to reduce this spending as soon as possible, and here enters the protagonist of this post, I’m open-sourcing LFS Proxy a pull-through LFS cache we created to store on S3 LFS objects and serve them to our CI pipeline as to save on GitHub LFS Bandwidth. Using this we reduced our spending from $3k/mo to $7/mo the S3 storage cost and there are no data transfer fees as long as we downloaded the data from within the same AWS region which we did.

In this post, I want to explain in as much detail as possible how LFS Proxy works internally leading us to these massive savings.

The one with the reverse proxy

When we started our journey trying to find a solution for the bandwidth issue, the first idea we had was to stop using Github as our LFS Server and go self-hosted, this way we could leverage existing infrastructure that we were already paying for. But the biggest issue with this was that CI is not the only thing pulling from git, we have engineers, game designers and artists pulling and pushing from the repo, so we would need to ask everyone to configure locally the LFS server and:

- A lot of people were using SourceTree as a git client as they are not engineers with console experience

- Even if you are tech-savvy, at some point someone will either change laptops or clone the repository on a different folder and forget to change the local

lfs.urlconfiguration and we will end up with a split-brain of content in between our hosted LFS and Github’s

So whatever solution we designed had to be completely transparent for people at the company. At the end of the day, the issue was mostly the number of times we checkout the repository on CI that’s the bulk of the bandwidth, people could continue using Github as they are not pulling a fresh copy of the repository 100s of times every day as we do on CircleCI they only pull whatever changed in between commits which is significantly less bandwidth than a fresh copy. So we focused on finding a solution specifically for CI without having to impact the company’s day-to-day in any way.

So now the challenge was, how can we have a hosted LFS server that we can run on our existing infrastructure for much cheaper than the GitHub Bandwidth costs, use it from CI to pull the binary content and keep it in sync with GitHub LFS Server so the rest of the company can just keep using that with no changes. I did some very thorough googling, trying to find something out there that did this with no results, found plenty of LFS Servers but none with an upstream sync functionality. So this meant we would probably have to develop something in-house.

I first did some investigation on how GitHub serves LFS content, using the GIT_TRACE=1 environment variable you can enable very verbose logs from git, and with it I found the following:

$ GIT_TRACE=1 git pull origin mian

22:25:41.579951 trace git-lfs: api: batch 100 files

22:25:41.580282 trace git-lfs: HTTP: POST https://lfs.github.com/org/repo/objects/batch

22:25:42.100440 trace git-lfs: HTTP: 200

22:25:42.100608 trace git-lfs: HTTP: {"objects":[{"oid":"<OID_HASH>","size":4263904,"actions":{"download":{"href":"https://github-cloud.githubusercontent.com/alambic/media////<OID_HASH>?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=<SNIP>%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=&X-Amz-Expires=3600&X-Amz-Signature=<SNIP>&

22:25:42.100627 trace git-lfs: HTTP: X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&actor_id=&key_id=0&repo_id=&token=1","expires_at":"2023-08-26T22:25:43Z","expires_in":3600}}}]}

I removed some data from the previous example for security purposes, but what I discovered with this is that GitHub is using an AWS presigned URL probably serving from CloudFront. So this turned a light on my head and gave me the following idea:

- We configure the git client on CircleCI to use a reverse proxy

- This proxy sends the request to GitHub and on the way back it uploads the requested content to S3

- Next time that specific content is requested is served back directly from our S3 bucket using a presigned URL.

This would also need to be able to mix-and-match content from GitHub and our own S3 bucket, for maximum cost-savings.

The diagram shows a simplified version of the flow:

- Request to download content from LFS is received

- For each file requested, check in-memory if we have a presigned link already available. If we do then add it to the response, if not then check if we have it on S3 and generate a new presigned link and cache it.

- For each file we don’t have cached on S3, request it from GitHub. Asynchronously in the background upload each file to our S3 bucket.

- Send out a response formed from both GitHub and presigned S3 links.

The one with the LFS API

The first thing we needed to do, was to understand how the LFS API works. We only cared about downloading content, so that made things a bit simpler for us. And luckily the Git LFS repository has pretty good documentation on the API.

The git client sends information to the LFS /objects/batch API endpoint, requesting the transfer of objects:

// POST https://lfs-server.com/objects/batch

// Accept: application/vnd.git-lfs+json

// Content-Type: application/vnd.git-lfs+json

// Authorization: Basic ... (if needed)

{

"operation": "download",

"transfers": [ "basic" ],

"ref": { "name": "refs/heads/main" },

"objects": [

{

"oid": "12345678",

"size": 123

}

],

"hash_algo": "sha256"

}

The only two pieces of information we care about here are operation and the objects list.

The operation is either download or upload depending on what the client wants to do, in our case we only care about requests for download.

The objects list is the list of objects to download, the OID (Object Identifier) and the size of it.

Then the server responds with the following:

// HTTP/1.1 200 Ok

// Content-Type: application/vnd.git-lfs+json

{

"transfer": "basic",

"objects": [

{

"oid": "1111111",

"size": 123,

"authenticated": true,

"actions": {

"download": {

"href": "https://some-download.com",

"header": {

"Key": "value"

},

"expires_at": "2016-11-10T15:29:07Z"

}

}

}

],

"hash_algo": "sha256"

}

Each object in the list has a href field that determines from where to download the object.

So what we would need to do on our proxy is to:

- Check if

operationisdownload - Loop over the list of requested

objectsand check if we have them on S3 - For every object that we don’t have, form a new modified request with the objects that we need and send it over to the upstream

- When we receive the response, loop over the returned

objects, in the background upload them to S3 and form a final response containing objects from both our own S3 bucket and whatever the upstream returned.

In our case the repository we use is private so authentication is needed, for this, we would just forward to upstream the credentials shared by the client.

Putting it all together

After understanding how the service would work, we were ready to get our hands dirty and develop it. We used Golang for all our services at Vela, so that was a no-brainer for us, for the HTTP Framework we decided on gin and for the cache we used bigcache an in-memory cache as we didn’t want to spend more on the infrastructure of a Redis deployment.

You can look at the full source code here

Deploying LFS Proxy

I currently don’t provide a public docker image for deployment, but there’s a Dockerfile, Helm chart and terraform module available in the repository that you can use. Once you have it deployed, you’ll need to configure your git client to use it:

git config --global lfs.url "https://user:password@lfsproxy.deployment.com/"

And there you have it, fellow wizards of efficiency and frugality! From the realms of reverse proxies and Amazon S3, we’ve emerged victorious, wielding a bandwidth-saving solution that not only lightened our digital load but also saved a princely sum each month. Now, as you wrap up this enchanting tale, consider this: the next time you approach your manager for a pay rise, just make sure to mention that your ingenious sorcery has put some extra $$$ in the company’s coffers. Who knows, a raise equal to the savings might just be on the horizon. Until our paths cross again, keep coding, keep innovating, and keep weaving your tech magic wherever you go! 🧙♂️🌟💰